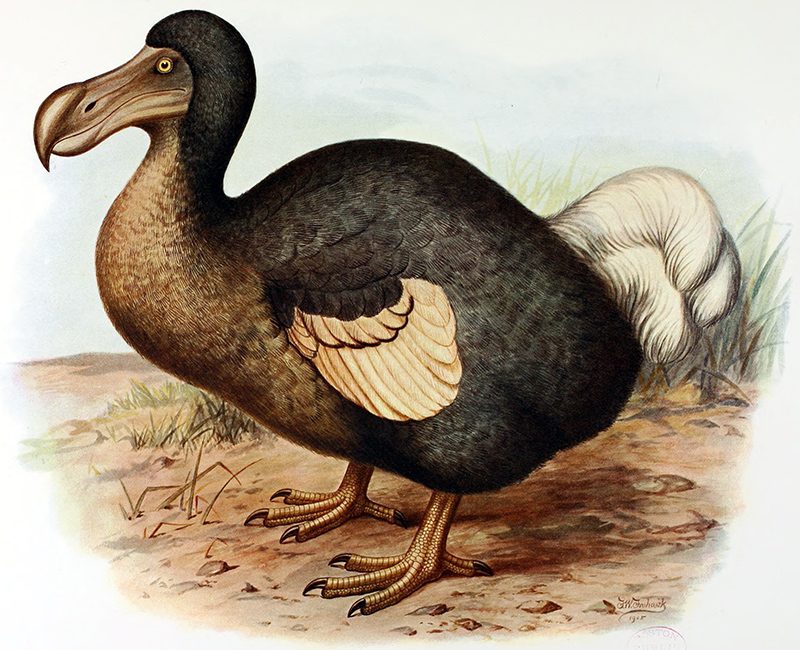

Frederick William Frohawk's restoration from Walter Rothschild's 1907 book Extinct Birds

Update: The Dodo bird may have survived for 30 years longer than was earlier thought. The last confirmed sighting was in 1662, but it is now believed that the last Dodo died in 1690.

The name Dodo comes from the Portuguese word for simpleton.

Dodo birds aided digestion by swallowing large stones; these were used by the Dutch sailors to sharpen their knives with. One of these stones, nearly an inch and a half in length, of extremely hard volcanic rock, is in the Cambridge University museum in England.

The Dodo was first encountered in the late 1500s or early 1600s and was probably extinct by the mid 1600s - as a result of human hunting, and especially the introduction of rats and pigs. The early accounts suggest that the animals did not recognise humans as a predator - and were easy to hunt.

The Dodo and Solitaire were so heavily modified for their island habitats (eg large, flightless) that it is very difficult to determine their evolutionary history by looking at their morphology (shape, e.g. bones). In fact early scientists had considered their closest relatives lay amongst parrots, birds of prey, shorebirds or pigeons - although by the 1800s the general view was that they were probably pigeons, or at least somewhat related to them. If they were pigeons, then the most likely explanation would be that they represented the descendants of migratory African pigeons that had lost their way and colonised the islands.

The Dodo and Solitaire were different enough morphologically that it was thought that they represented independent colonisation events - from differing African pigeons. Interestingly, recent work by Andrew Kitchener of the Royal Museums of Scotland, has showed that the Dodo was probably not as fat as generally depicted in the paintings of the time. Most of these were copies, or not based on original observations - and many may have been based on birds in captivity in Europe - where they may well have been overfed by people not familiar with their ecology.

Research published in Science by a team from Oxford University and the Natural History Museum, London, has shed new light on the genetic origins of the Dodo as well as offering solutions to how the species bird came to be isolated on the island of Mauritius.

Despite being the emblem of extinction, the evolutionary history of the Dodo is poorly understood. The extreme evolutionary changes it has undergone (e.g. gigantism, flightlessness) on the island of Mauritius have even concealed its closest relatives within the birds - and it has been linked with everything from parrots, pigeons, and shorebirds, to birds of prey.

Dr Alan Cooper and Dr Beth Shapiro from Oxford's Henry Wellcome Ancient Biomolecules Centre, Dr Dean Sibthorpe, Andrew Rambaut, Dr Graham Wragg, Dr Olaf Bininda-Emonds and Dr Patricia Lee from Oxford's Department of Zoology, and Dr Jeremy Austin from the Natural History Museum, London, carried out the research, by retrieving tiny fragments of Dodo DNA. The samples were taken from the only surviving Dodo specimen with soft tissues remaining - the 300 year old 'Alice in Wonderland' specimen in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History - so called because it was the inspiration for the character in the Lewis Carroll book.

The Dodo DNA (taken from small pieces of skin and leg bone) was compared to 1400 base pairs (units of DNA length) of gene sequences from the Solitaire, an extinct Dodo-like bird from neighbouring Rodrigues Island, and 35 species of pigeon and doves, as well as other bird groups. The DNA showed that the closest living relative to the Dodo and Solitaire was the Nicobar pigeon, from southeast Asia - and that the next nearest relatives were the crowned pigeons of New Guinea, and the unusual tooth-billed pigeon of Samoa.

Dr Alan Cooper, Director of the Henry Wellcome Ancient Biomolecules Centre, described how the species became distinct from each other, saying: 'The genetic differences suggest that the ancestor of the Dodo and Solitaire separated from the Southeast Asian relatives around 40 million years ago, and sometime after this point flew across the Indian Ocean to the Mascarene Islands. The data suggest that the Dodo and Solitaire speciated from each other around 26 million years ago, about the same time that geologists think the first (now submerged) Mascarene Islands emerged. However, Mauritius and Rodrigues islands are much younger (8 and 1.5 million years respectively), implying that the Dodo and Solitaire used the now sunken island chain as stepping-stones. Furthermore, the isolation of Rodrigues Island suggests that the Solitaire, at least, may have still been able to fly as recently as 1.5 million years ago.'

The Henry Wellcome Ancient Biomolecules Centre determined the first complete mitochondrial sequence of any extinct animal in February 2001. The sequence of a moa, a giant ratite bird from New Zealand was determined by staff at Oxford and the Natural History Museum, London, and the University of Barcelona.

Part of the Dodo study was also replicated at the Natural History Museum, London - to authenticate the ancient DNA results, which are notoriously prone to contamination.

The 'Alice in Wonderland Dodo' is held at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. It consists of a head (with skin) and a leg and foot (also with skin) - and represents the only known surviving soft tissues of a Dodo. The entire specimen is thought to be one of the birds brought to Europe for exhibition in the mid-late 1600s, and was almost thrown away in a museum clean-up of tatty specimens in the 1700s. Fortunately, a curator grabbed the leg/foot and head (reputedly from the fire used to dispose the rejects). The museum kindly gave permission to sample a piece of bone from the leg and a small section of flesh from the head. Relatively few well-preserved specimens of the Dodo exist - although a number of bones have been retrieved from the large swamps in Mauritius. Unfortunately the swamp environment has not allowed the preservation of DNA. Researchers also examined bone from the Solitaire, a large Dodo-like bird from Rodrigues island, which lies some distance to the East of Mauritius. Jeremy Austin, the London based co-author, collected the Solitaire bones from limestone caves on Rodrigues as part of his research on giant tortoises. The cave preserved material was in much better condition even than the 'Alice' specimen - probably because the latter has been on display off and on for over 150 years (under lights and in warm conditions). Studies continue of these strange birds of the island of Mauritius